- Home

- C. J. Farley

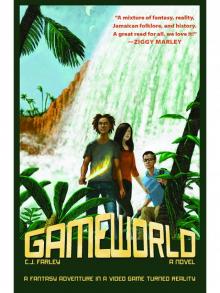

Game World Page 6

Game World Read online

Page 6

The hummingbirds hovered lower, their swords glinting in the sunlight.

“This is a restricted area,” chirped a hummingbird with a patch over one eye and the number 757 on his chest. “You’ll need to pay one hundred wishcoins—each.”

“Is a wishcoin like money?” Dylan asked.

One hummingbird with the number 182 on his chest and a voice gruffer than any hummingbird had a right to have guffawed. “They’re much more than money. Wishcoins are how anyone pays for anything around here. Collect a million of ’em and they’re good for one wish from the Iron Lions.”

“A million? That sounds like a lot,” Eli said.

“Not for birds,” the patch-eyed hummingbird twittered.

“Why are you guys so rich?” Eli asked.

“We manage everyone’s wishcoins,” the gruff-voiced bird declared.

“So you get paid the most because you hold on to everyone else’s pay?” Eli said.

“We take all the risks,” the patch-eyed bird explained. “It’s only fair.”

“What kind of risks are you taking?” Eli asked.

“Gambling, of course,” the gruff-voiced bird chirped. “What else would intelligent creatures do with their riches?”

Eli looked incredulous. “What happens when you lose?”

“Why, then we have a wishcoin support program. The whole kingdom contributes. It wouldn’t be right for the creatures who are taking all the risks not to have a safety net.”

Eli shook his head. “So if the kingdom gives you a safety net, shouldn’t you share the wealth?”

The two birds looked at each other.

“If I weren’t paid enormous sums for what I do,” the gruff-voiced bird huffed, “why would I even get out of my tree in the morning?”

“The long day is breaking, so my bath I am taking,” said the ridiculously loud voice from before.

Dylan and his friends covered their ears, their skulls throbbing with the sound, but the birds didn’t even blink. Dylan wondered if birds could blink. He should have paid more attention to the Professor’s lectures.

Ines moaned: “That voice is annoying!”

The two birds both shook their heads. “They don’t know about the Grand Chirp,” the gruff-voiced bird squawked.

“The Grand Chirp?” Eli asked. “That’s a thing?”

“How else would we know what Baron Zonip is doing?” the gruff-voiced bird replied. Just then, its number fell from 182 to 2,896, and the patch-eyed bird’s rose from 757 to 500. “Kiss my tail feathers!” the gruff one cursed.

“What do those numbers mean?” asked Dylan.

“The Baron ranks every bird in the kingdom,” the bird explained.

“Based on what?” Eli asked.

“Two things: Whatever He Thinks and None of Your Business.”

“Something tells me they’re not from this branch of the world,” the patch-eyed hummingbird chirped suspiciously. “We’d better take them in.”

* * *

The birds marched them away.

Dylan found it fascinating to see birds marching, particularly hummingbirds, who aren’t naturally given to flying in formation, much less belonging to military organizations. On the ground, soldiers march in straight lines. How pedestrian of them. In the air, the hummingbird brigade flew in ever-changing three-dimensional geometric patterns—shifting spheres, rotating cubes, spinning pyramids. The effect was kaleidoscopic and mesmerizing and would have also been entertaining had Dylan not been the center of this flying formation, held as an unwilling, unflying, unhappy prisoner.

Dozens of the birds had grabbed hold of each of them and carried them aloft like laundry on a line. In the video game, areas of Xamaica were separated by levels and players could only visit a small region of the island. Now Dylan could see for miles. He, Eli, and Ines swept past the waterfalls, a veil of golden mist against the green face of the hills. They were traveling along the coast, where the crimson clay of the land met the blue of the sea. With all this space, Dylan wondered, how would he ever find his little sister? What was the line Emma had quoted? Everything you can imagine is real. Dylan began to think that maybe this was all real in some way. If he could just get his powers back—even a bit of them—he could find clues about Emma.

“When we play Xamaica back on Earth, we only get to travel in the gray lands,” said Eli, who was being carried, wheelchair, laptop, and all, by a squadron of hummingbirds. “I think they’re over there—shrouded by mist with the Moongazers all round.”

Dylan looked down. “You can see creatures disappearing and reappearing in the mists! I’m guessing that when you play the game, your avatar appears in this world. When you log out, it blinks back out.”

“So where are our avatars?” Eli asked.

“No clue. I could sure use the Duppy Defender right now.”

“Do they have any air sickness bags on this flight?” Ines groaned. “I’m gonna hurl.”

Eli laughed. “I’ll never watch your show the same way again. Not that I was watching it much before.” He tapped the helmet of the patch-eyed bird—one of the many hummingbirds carrying him. “Can’t you go faster? And can we get a closer look at some of the territory down there?”

Big mistake.

The birds all went into a steep dive, and Dylan felt like he was heading down the craziest roller coaster ever. He tried to stay focused on the land below. The game Xamaica clearly didn’t impact the real Xamaica, except along the fringes. Playing Xamaica the game was like visiting Ellis Island without seeing Manhattan—it was just an entry point into something bigger and more sweeping. Dylan hadn’t seen any of the avatars of the kids he had met while playing the game. But none of them had reached beyond the forty-third level. The time he had managed to inch onto the forty-fourth level and carve his initial into the palm tree was the only mark he had ever left on Xamaica. He was in totally unmapped territory, and somehow, someway, he had to find his sister.

Ines had squeezed her eyes shut. “Tell them to stop!”

Eli was scared too but tried to play it cool. “Who is this Baron Zonip they’re tweeting about?” he asked Dylan. “Is he their leader or something?”

Dylan started chewing his fingernails. “I just hope he knows where my sister is.”

Building speed, the procession passed over a field of flowers. Giant bees in tan uniforms—workers?—flitted below. The flowers were massive, the size of lampposts. The smell was amazing—like breathing sunlight. Soon, a mighty forest of trees appeared in the distance. The physics of this world were different—things could obviously grow taller, wider, and brighter. The forest was made up of palm trees, but they were the size of skyscrapers. And above, over the fronds, a small city was constructed. There were buildings and passageways, storefronts and houses, all balanced on branches by some incredible architectural skill or magic. And above all floated a vast green cloud, full and fluffy as a mattress stuffed with money.

“Ssithen Ssille—the legendary hummingbird kingdom!” Eli shouted. “In the game, I thought this place was just a rumor!”

Now the brigade of birds was flying in dizzying loops trying to intimidate their involuntary guests. But Dylan stayed focused on what he was seeing. Ssithen Ssille was magnificent, astounding, and all those adjectives and phrases people generally pull out when they see the Grand Canyon for the first time, or Mount Rushmore or the Taj Mahal. Dylan felt like he was seeing all of those places together, with the Empire State Building and the Great Wall of China thrown in for good measure. The view before him was the Seven Wonders of the World—squared.

They overheard the warrior birds chirping some basic information about the city, but the sights spoke for themselves. In fact, they shouted for themselves, and the words echoed in the wind. Before them was the Golden Grove, a stand of mahoe trees with silver trunks, platinum branches, and golden leaves. Each tree was the size of a city block, maybe bigger, and all were made of a magical alloy that kept them supple and gloriously alive as they sw

ayed gently in the wind. The children were told that each tree belonged to a particular hummingbird clan, and they were handed down from generation to generation. Dylan could see whole communities of birds tucked away in the shining branches—buildings and baths and porches and all the kinds of things you might see in gated communities and exclusive neighborhoods back on Earth. This was the ultimate high society. Dylan had never seen a forest like this one.

“Talk about your family trees,” Eli said.

They were now zooming into the heart of the Golden Grove. Ines’s hair was flapping in the wind, and Eli was clutching at his glasses to keep them from flying off. On the tops of seven trees clustered together was a grouping of massive nests. In each nest were eggs—not just a couple eggs, not just a dozen, but possibly thousands, all of them green with yellow spots, and arranged in intricate fragile piles. Storks dressed in sterile-looking white uniforms—Dylan figured they were doctor birds—hovered around the eggs. There was a commotion atop one of the trees and several of the doctor birds fluttered closer. As the brigade turned away, Dylan caught a glimpse of a baby hummingbird emerging from its shell.

The hummingbird city stretched on for more than a mile. At the center of the vast urban grove was a towering tornado. The twister spun and raged but remained in a single spot, surrounded by a swirl of branches, leaves, and dust. At the top of this tower of wind was a castle fortress—the structure was motionless, but it was encircled by a barrier that spun around like a roulette wheel. In fact, the wall seemed to be a massive game of chance—there were chicken scratch–like markings along its sides that may have been numbers, and a big golden egg tumbled on top of the enclosure as it spun, coming to rest, from time to time, in one spot or another. At such moments there would be a surge of bird wails accompanied by a matching number of delighted twitters, and the birds soaring in the air or perched in the branches would settle their bets, or so Dylan guessed, since whatever currency they were exchanging was invisible to his eyes.

The birds flew their prisoner-guests over the spinning barricade, under a huge arch adorned with giant stone birds with outstretched wings on either side, and then through a glittering white passageway, before landing in a high-ceilinged, gem-encrusted room. There, the birds let Dylan, Eli, and Ines stumble to their feet. With his one good eye, the patch-eyed hummingbird winked and flitted away.

Ines flicked her hair back into place. “They didn’t even give us an in-flight snack.”

They glanced around. In the center of the room was a globe filled with huge worms.

“Welcome, guests, to my humble nest,” said a voice, louder than all thunder.

There, at the end of the great chamber, was a hummingbird. It reminded Dylan of the time he went with the Professor and Emma to visit the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC. This hummingbird, like that famous Lincoln statue, dominated the room, filled it up, suffused the walls with his presence. It was clearly the master of all things with wings. It radiated wisdom and benevolence and made Dylan wonder if the term birdbrain was more of a compliment than an insult.

The great bird had to be Baron Zonip.

This most regal of hummingbirds had a throne that was a nest made of gold leaves. It didn’t seem comfortable, but it certainly looked expensive. On the left side of the bird king was something that appeared to be a silver seashell. The bird king had just been speaking into it, so Dylan reasoned that it must be what the bird used to broadcast the Grand Chirp. On the right side of it was a huge drum, several times larger than Dylan, decorated with pictures of spiders. Was it a gift from some delegation of arachnids? Or the spoils of war?

This is bird-watching heaven, Dylan thought. The Professor would love this.

The scratches on his chest throbbed. He tried to ignore the pain.

All around the room were murals depicting the hummingbird king and his heroic adventures—helping chicks under attack, defeating evildoers, and saving Xamaica (and countless eggs) repeatedly. There was also a gilded mosaic celebrating the work of the hummingbird nation. It showed various creatures giving treasures to the birds to count and store. The birds took in real valuables and handed out tokens—Dylan figured they were wishcoins. In every picture, the hummingbird’s nests, buildings, and palaces were filled with stacks of the glittering coins.

On either side of the Baron stood two guards, beaks tipped with serrated silver blades. On a small stand near his throne were stacked some dog-eared books. Dylan quickly scanned the titles: Thus Chirped Zarathustra, The Invisible Talon: Avian Economic Theory, and To Kill a Mockingbird: Modern Methods of Capital Punishment.

But the children’s eyes were captivated not by the books or the murals or the guards, but by the Baron himself. There was something innately elegant about his movements; he had an undeniable imperial quality. His plumage was black, yellow, and green, and he had swooshing tail feathers that were longer than the rest of his body. He wore a black coat that almost looked like a tuxedo jacket with tails. His broad red chest was crisscrossed with two black sashes. Balanced on his beak was a pair of ink-black circular glasses. And on his head, he wore a top hat with a glowing gold number in the middle: 1.

The kids stood before the Baron of Birds, the King of Clouds, the Emperor of Air.

The Baron was every inch a monarch—though there weren’t that many inches to him.

Although some of the other hummingbirds were relatively huge as far as hummingbirds go, the Baron, ruler of them all, was not a big bird. He wasn’t even a medium-sized one. In fact, he was even smaller than a normal Earth hummingbird, which is to say a little shorter than this sentence.

At first, Dylan was taken aback by the king’s small stature. But then again, Napoleon was short. So were Alexander the Great, John Adams, James Madison, 99 percent of all movie stars, and 100 percent of Gandhi. So why not a teeny-weenie bird baron?

“Let me do the talking,” Ines said to the others. “On my show, I’ve met three presidents and two popes. Or is that a pair of presidents and three popes? All I remember is two of them were wearing funny hats.”

The Baron spoke into his seashell: “I think I am giving my guests a drink.”

The children tried in vain to cover their ears. The Grand Chirp was even louder when you were this close to the Grand Chirper. “You don’t have to use that, we’re standing right here!” Eli yelped.

“I know, right?” Ines moaned, rubbing her ears.

“I am Baron Zonip!” the Baron declared. His voice—sans the seashell—was a tiny tweet. Dylan had to bend forward and cup a hand to his ear just to hear it.

With that, the Baron grandly motioned to his court, and Dylan, Ines, and Eli were each handed a long-stemmed flower. The bulb of each was filled with an emerald liquid substance the consistency of syrup.

“I think we’re supposed to drink this,” Dylan said.

Eli stuck out his tongue. “Gross!”

“I had to eat a lot worse when I filmed an episode in Libya,” Ines said. “Trust me, camel brain doesn’t go down easy. Bottoms up!”

She raised her flower to drink and Dylan and Eli did the same.

“It’s some kind of nectar,” Eli said, licking his lips. “It’s like the best soda crossed with the greatest sports drink ever!”

“No, it’s more than that—it’s something magical!” Dylan said.

An almost impossibly happy vision filled Dylan’s mind as if it were happening to him right then and there. He was a young Iron Lion and he was flying for the first time. Feeling the wind against his wings was a thrilling joy—like his whole body was smiling.

“I’m feeling it too,” Ines said. “In my mind, I’m a Wata Mama in a clear cool stream.”

“I’m a Steel Donkey, eating my first bucket of iron oats,” Eli added. “The nectar—it’s like liquid memories.”

The Baron laughed with glee as he saw the children enjoying the nectar. And if you’ve never heard a bird laugh—it’s a breezily charming sound, almost like wind chimes, and it’s hard not

to smile along. “We call the drink Sslinder Sslee,” he chirped. “We milk it from the Green Cloud.”

“I think we saw the Green Cloud! Where does it come from?” Ines asked.

“Let’s just call it our intellectual property!” the Baron laughed.

The Baron’s helpers brought more flowers to drink. The refreshments were surprisingly filling—the kids soon felt stuffed, and their heads were spinning with magic memories. After a polite pause, the Baron motioned for them to introduce themselves.

“I’m Dylan.”

“I’m Eli.”

“And I’m Ines Mee. My name was the twenty-seventh most searched-for term on the web last year.”

Eli shook his head. “I don’t think he needs to know that.”

“I have many fans on the Net,” Ines huffed. “I won’t apologize for it.”

“Tell me: are you from Babylon?” the Baron inquired.

“People keep asking that,” Dylan said. “What’s Babylon?”

“A place of illusion—of fossil fuels and supermodels, of plastic surgery and paper money.”

“You say it like those are bad things,” Ines grumbled.

“If Babylon is what you call Earth, yeah, we’re from there,” Dylan said.

Eli raised a fist. “Brooklyn in the house!”

“You’re from New Rock just like me!” Dylan whispered to Eli.

“The bird doesn’t know that,” Eli whispered back. “I’m just trying to get us some street cred!”

“What are you doing in Xamaica?” the Baron asked.

“I’m searching for my sister—her name is Emma,” Dylan explained. “She’s a human girl, about yaaaaaay high, with braids. She likes to quote people that nobody’s heard of who probably died thousands of years ago anyway. Have you seen her?”

“You are the first humans we’ve seen in many moons. But I will spread the word among my people to keep watch for this . . . Emma.”

Dylan wanted to ask the Baron how he could trigger his powers and why the cheat code wasn’t working. But Ines and Eli didn’t know about the code, and something told Dylan he shouldn’t go telling every creature he met that he was powerless.

Game World

Game World